Anyone familiar with SLC's architectural culture has undoubtedly admired the work and legacy of John Sugden [1922-2003]. Mr. Sugden could easily be the most intensely complex cocktail of prestigious education, apprenticeship, and design philosophy that Salt Lake has ever seen. Born in Chicago, where his father was attending medical school, the family returned to their native Utah when he was still an impressionable kid. An intimate connection between Sugden and Utah's landscape formed via adventures in rock climbing, skiing, and explorations with his naturalist father.

John eventually returned to Illinois to pursue professional training at the Illinois Institute of Technology. It's there that he landed himself under the world-renown wings of architects, Mies van der Rohe and Ludwig Hilberseimer. Tutelage under these iconic, 20th-century creators propelled Sugden to a caliber of design [and, ultimately, a body of work] for which most architectural students would trade their lives. Mies was among the most influential and thought-shifting designers of American skyscrapers after World War II, transforming common ideologies into works of architectural ingenuity. Two of the most well known are the Seagram Building in New York [1958] and the 860-880 Lake Shore Drive buildings in Chicago [1941-1951], on which John was able to work alongside Mies as project architect. Both projects stand today as well-recognized and highly-regarded monuments of modernism for scholars and architects around the world.

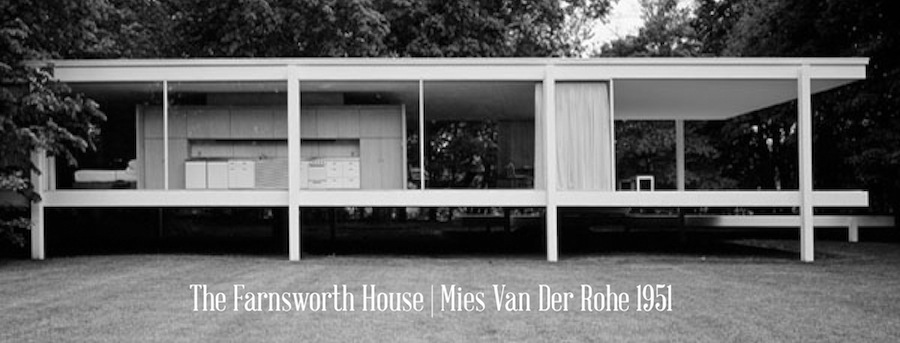

Sugden's final project, and the completion of his apprenticeship under Mies, was his work on the Farnsworth house in Plano, Illinois. A significant structure that has since been purchased by the National Trust, the philosophy behind the project is best worded by historian, Maritz Vanderburg: “Every physical element has been distilled to its irreducible essence. The interior is unprecedentedly transparent to the surrounding site, and also unprecedentedly uncluttered in itself. All of the paraphernalia of traditional living – rooms, walls, doors, interior trim, loose furniture, pictures on walls, even personal possessions – have been virtually abolished in a puritanical vision of simplified, transcendental existence. Mies had finally achieved a goal towards which he had been feeling his way for three decades." It would seem that Sugden packed these concepts securely in his suitcase before boarding the flight home.

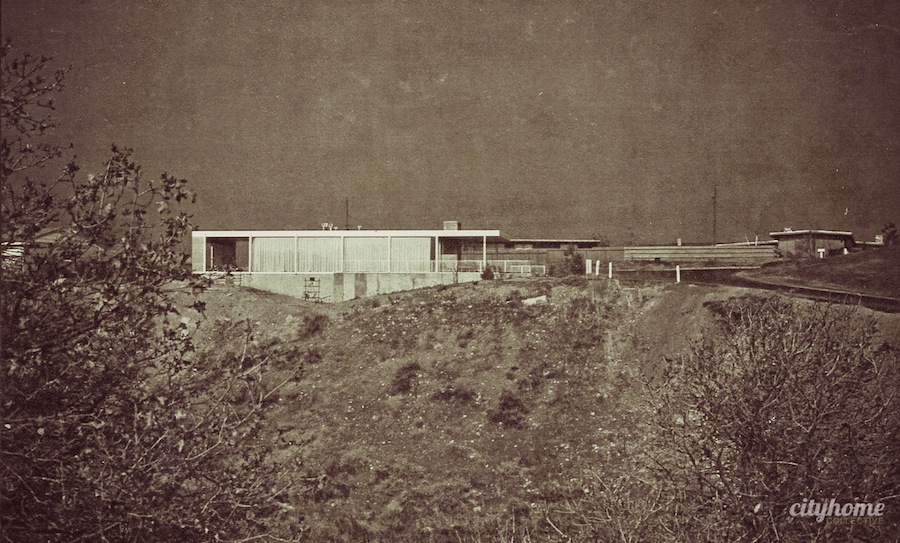

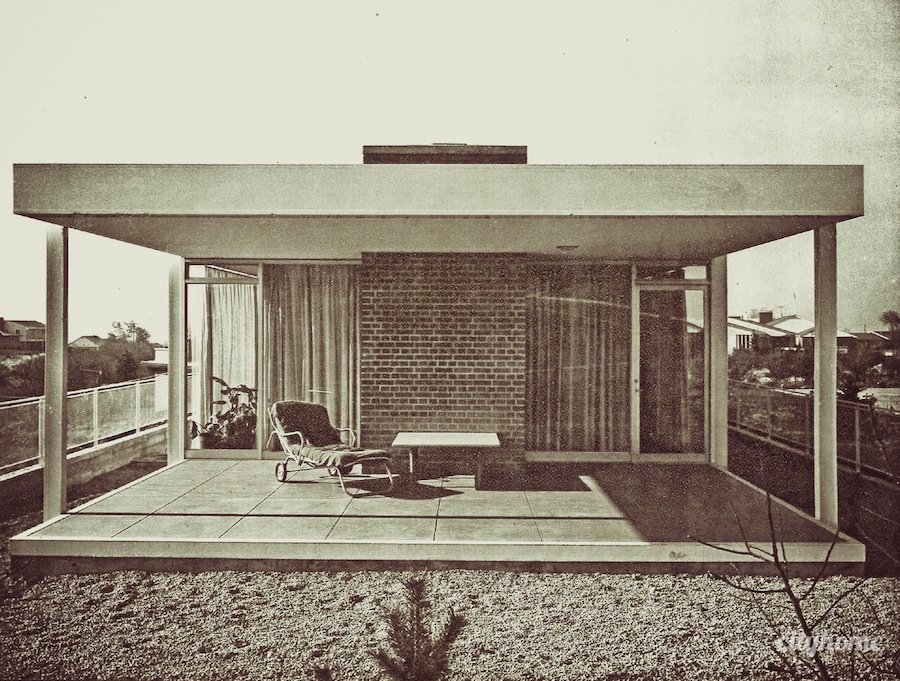

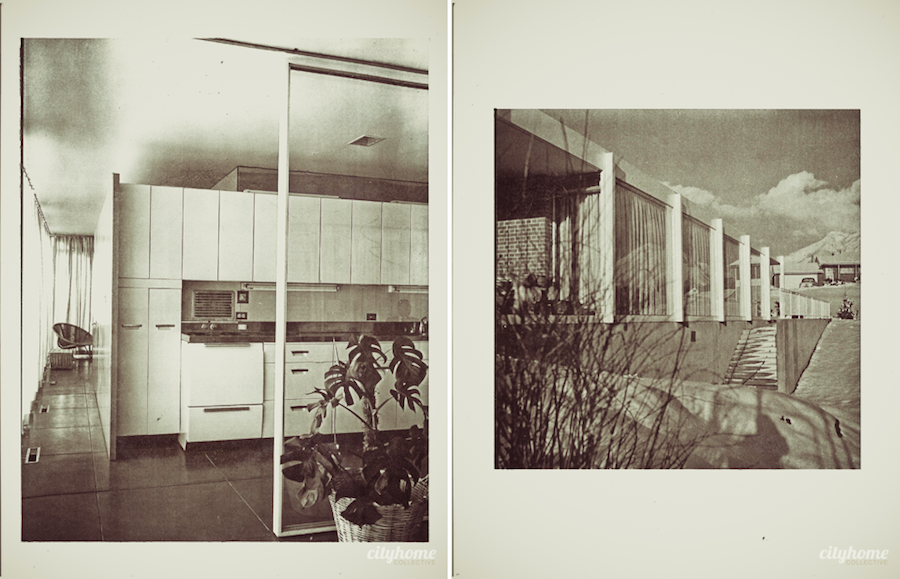

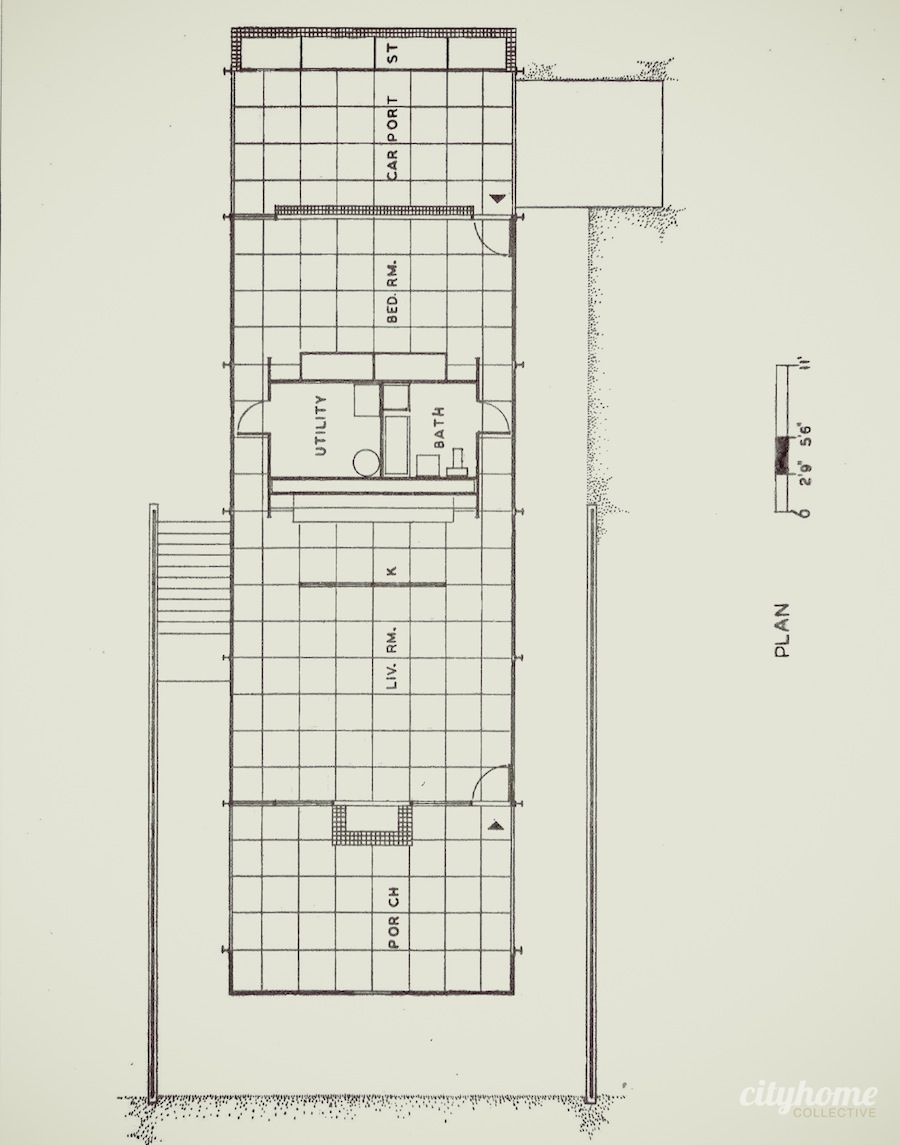

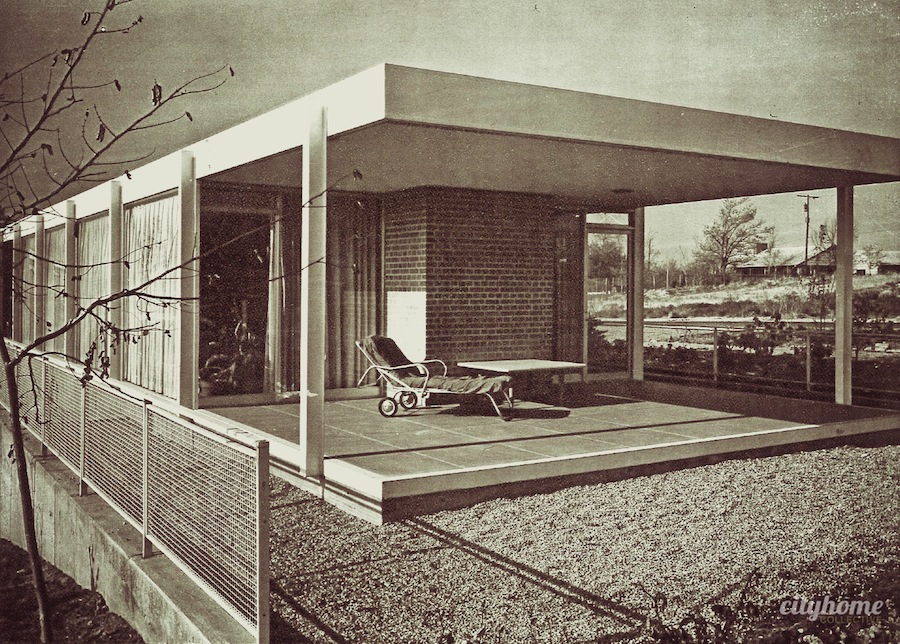

John's first project upon returning to Salt Lake was a home built for his mother in 1955. This inaugural undertaking contains all the inspirational elements of the Farnsworth home: floor-to-ceiling glass supported by once-white steel framework; the classic design of utility closet, storage, and kitchen serving as an anchor for the home; bedroom, dining, and living spaces each stretched outward; the delight of living encased by nature and the elements. Originally built on what could be described as a prairie, planted foliage has since grown around the home, acting as a living curtain that gives a sense of privacy in intimate connection with the seasons.

The current owner, Molly, purchased the home in 1993, becoming the third owner and savior of this modern landmark. The landscaping had run amok, windows were covered in drapes, and the previous owner had made an addition that largely distracted from the original design. Years of work, however, and diligent consultation with friend and Sugden colleague, Dee Wilson, enabled Molly to mold a consistent design with the addition, pull back the encroaching foliage, and save this building from the likely fate of purchase and demolition. For her efforts, she was honored with a well-deserved Utah Heritage Foundation Award in 2005.

It's been said of Mies by The National Trust, "In the United States, after 1938, he transformed the architectonic expression of the steel frame in American architecture and left a nearly unmatched legacy of teaching and building." That noted, Salt Lake should be honored to have a piece of that legacy continued and interpreted by the talented mind of John Sugden. His incredible contributions to our city have been a pillar of design inspiration since his very first construct, and, to this day, they stand uniquely as living museums in significant Salt Lake architecture.

Information Sites: Anne G Mooney | Utah Heritage Foundation | National Trust